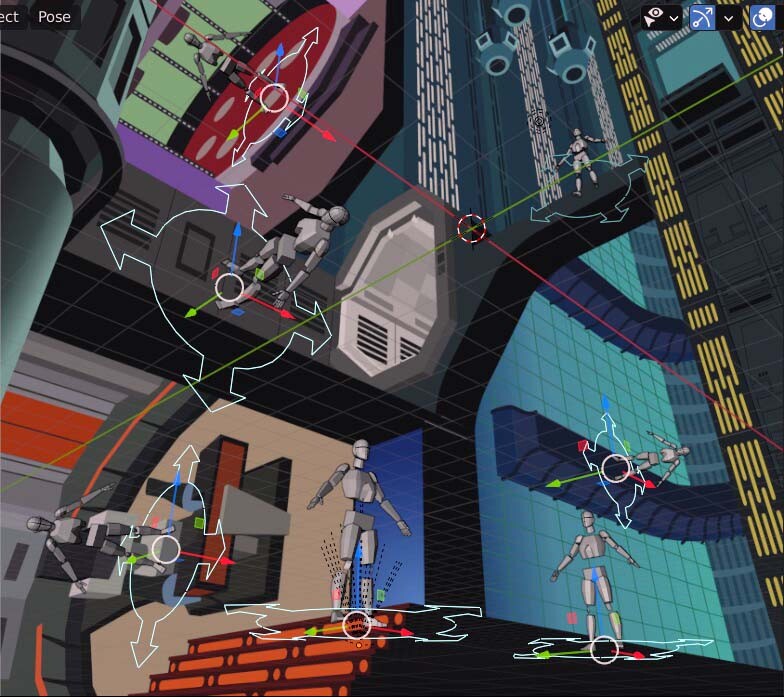

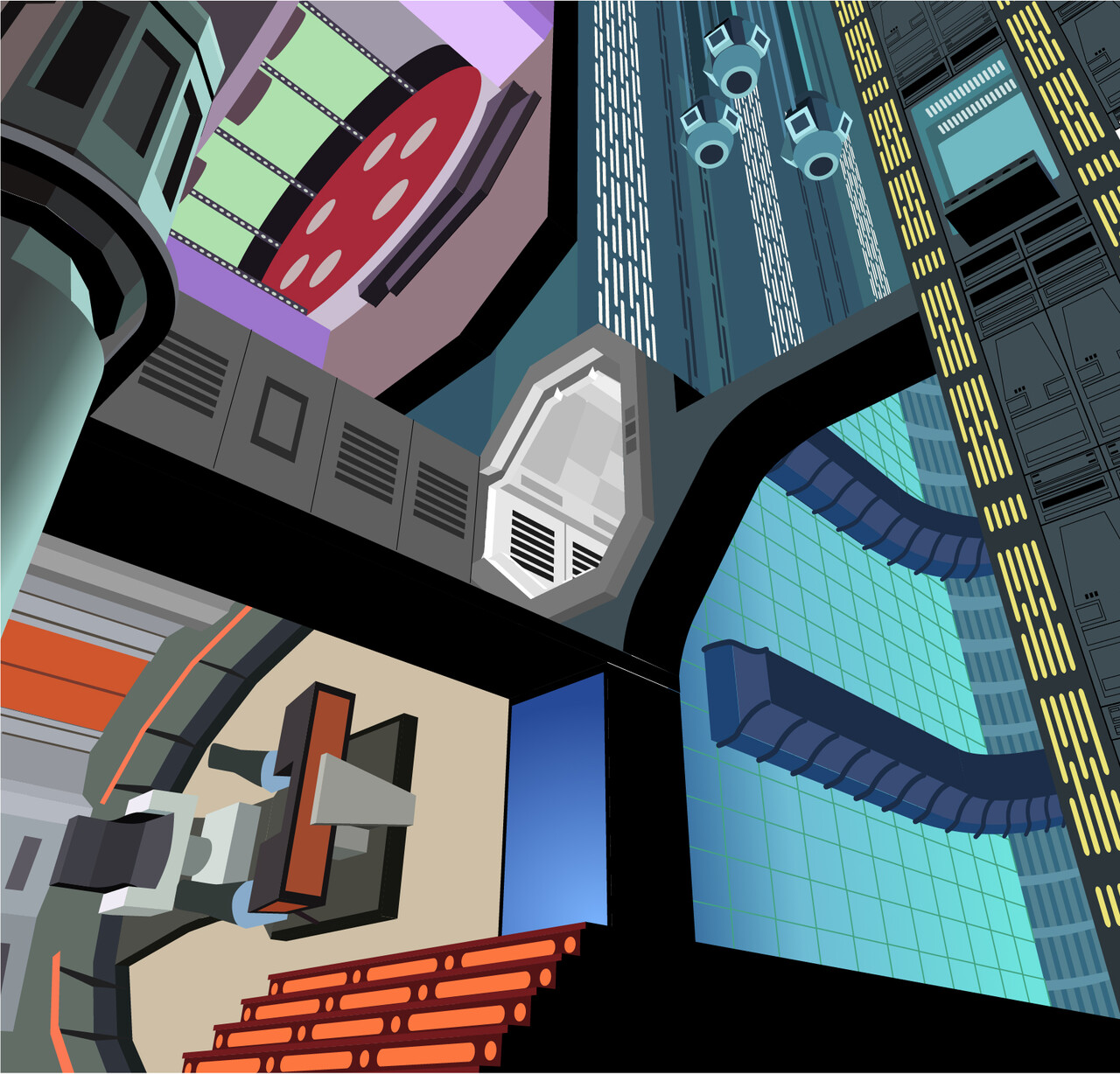

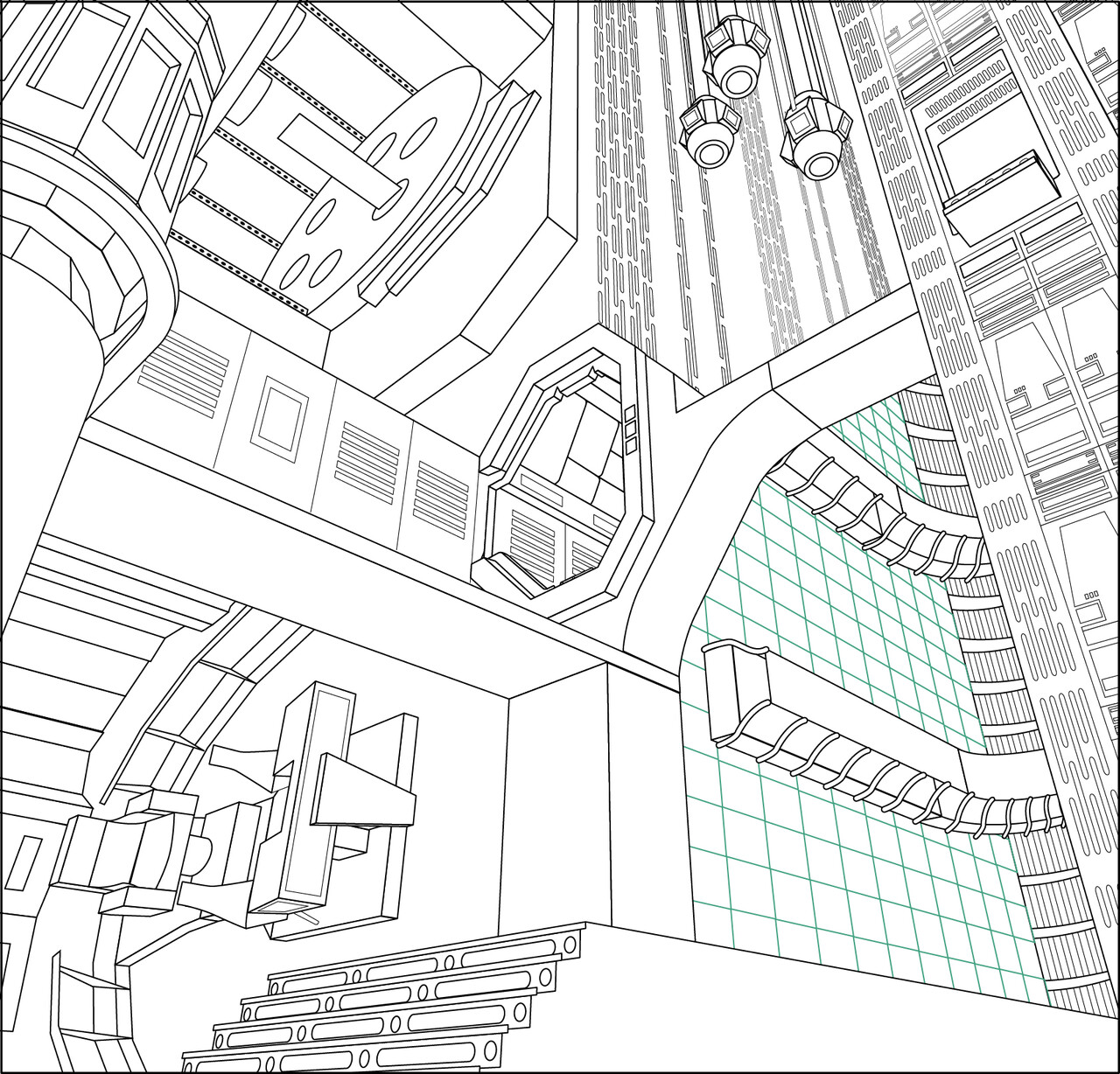

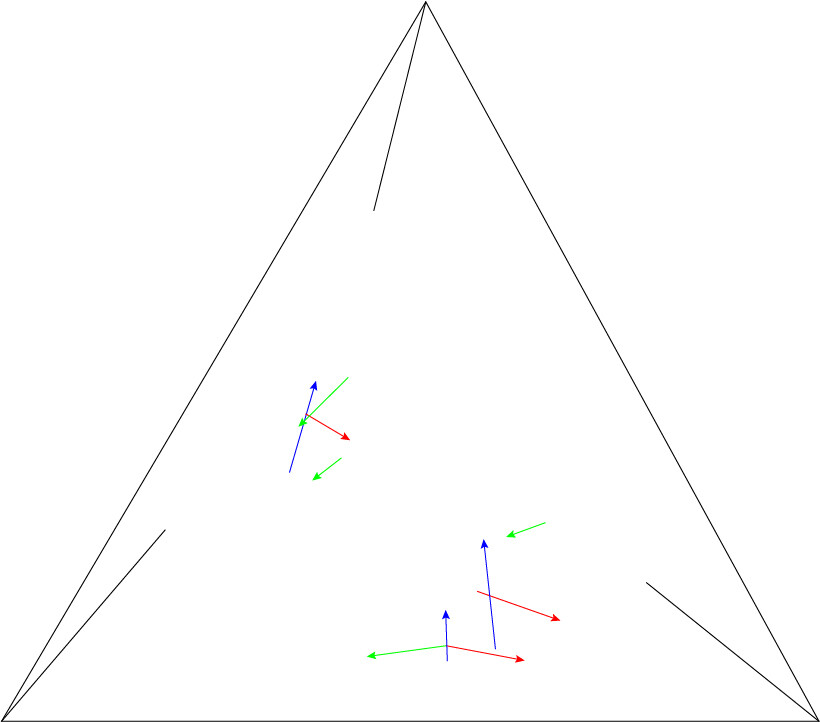

After all of the work in Illustrator, Blender and fSpy, I was looking forward to doing some drawing.

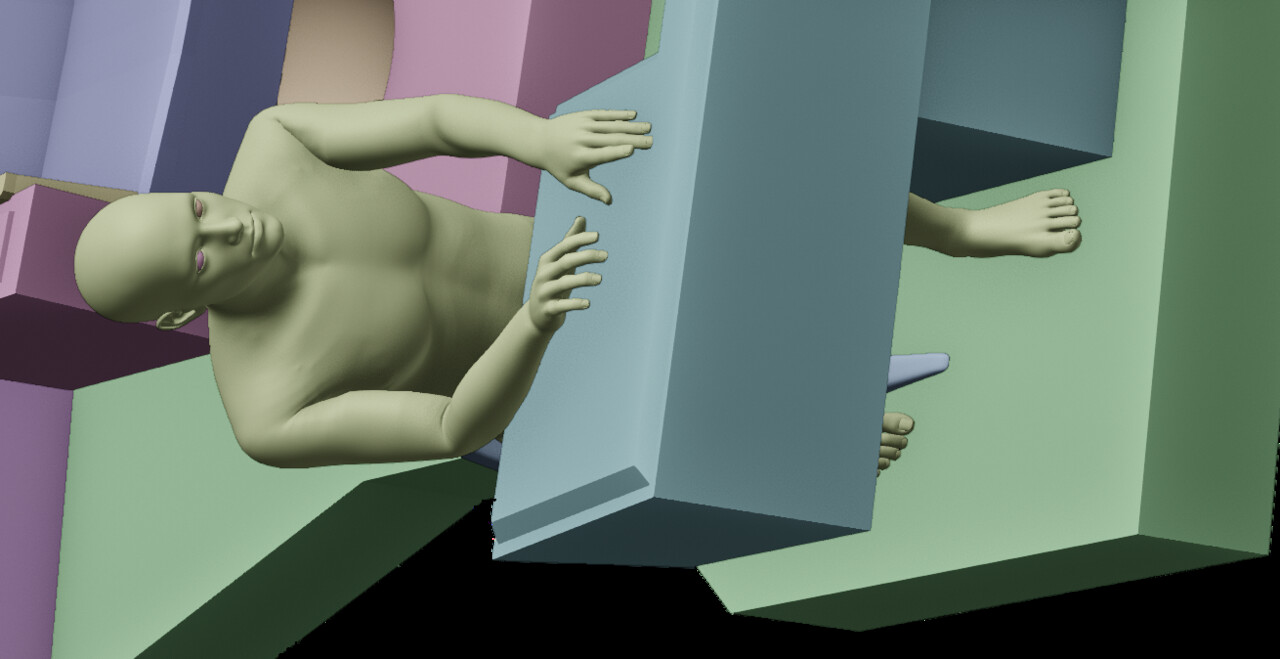

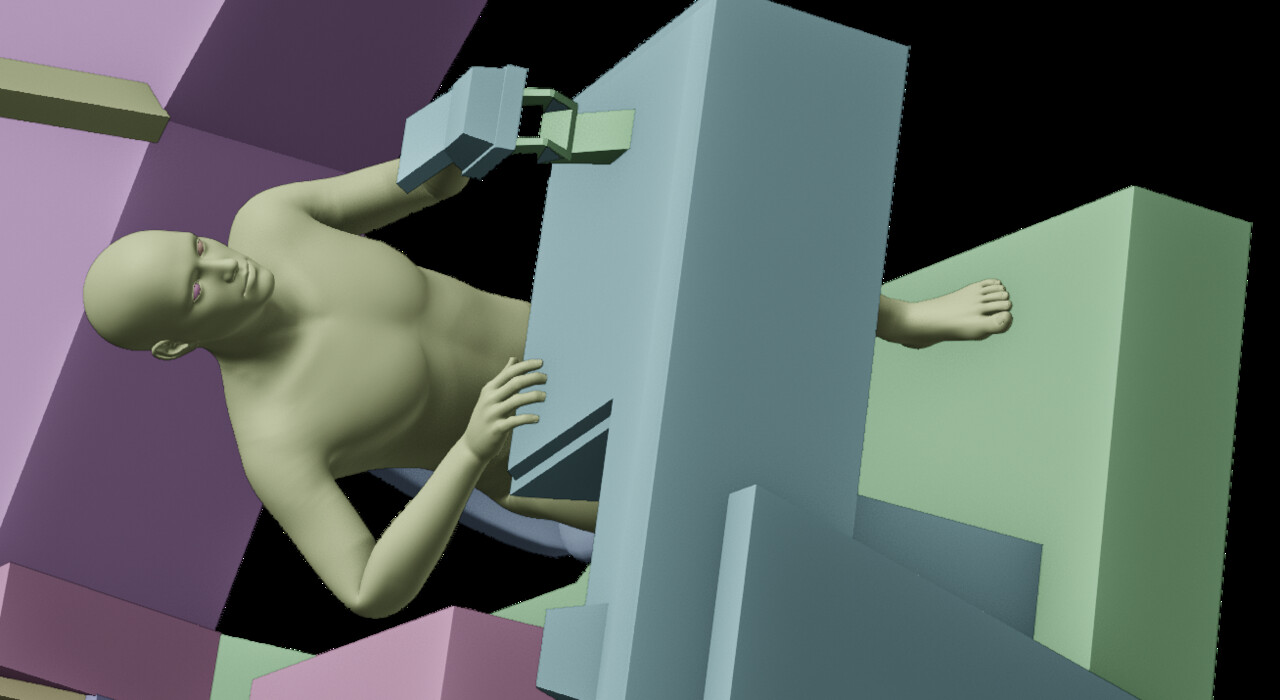

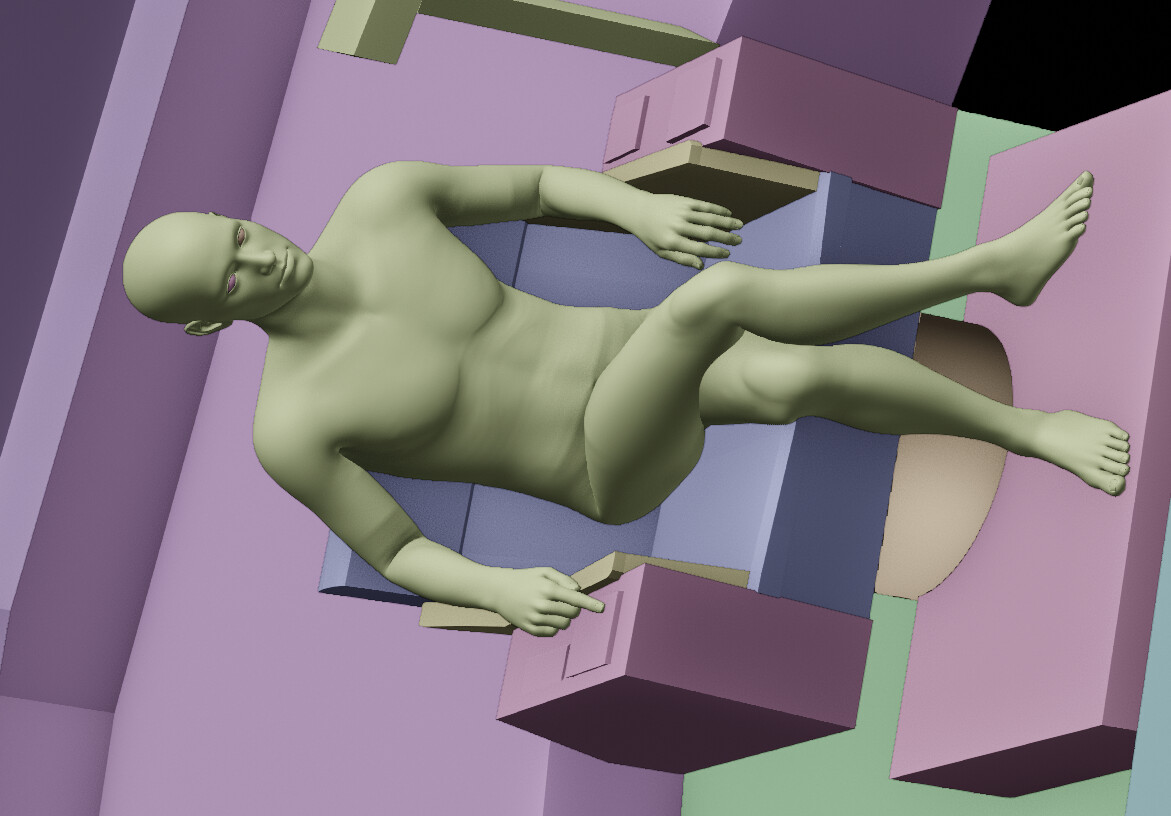

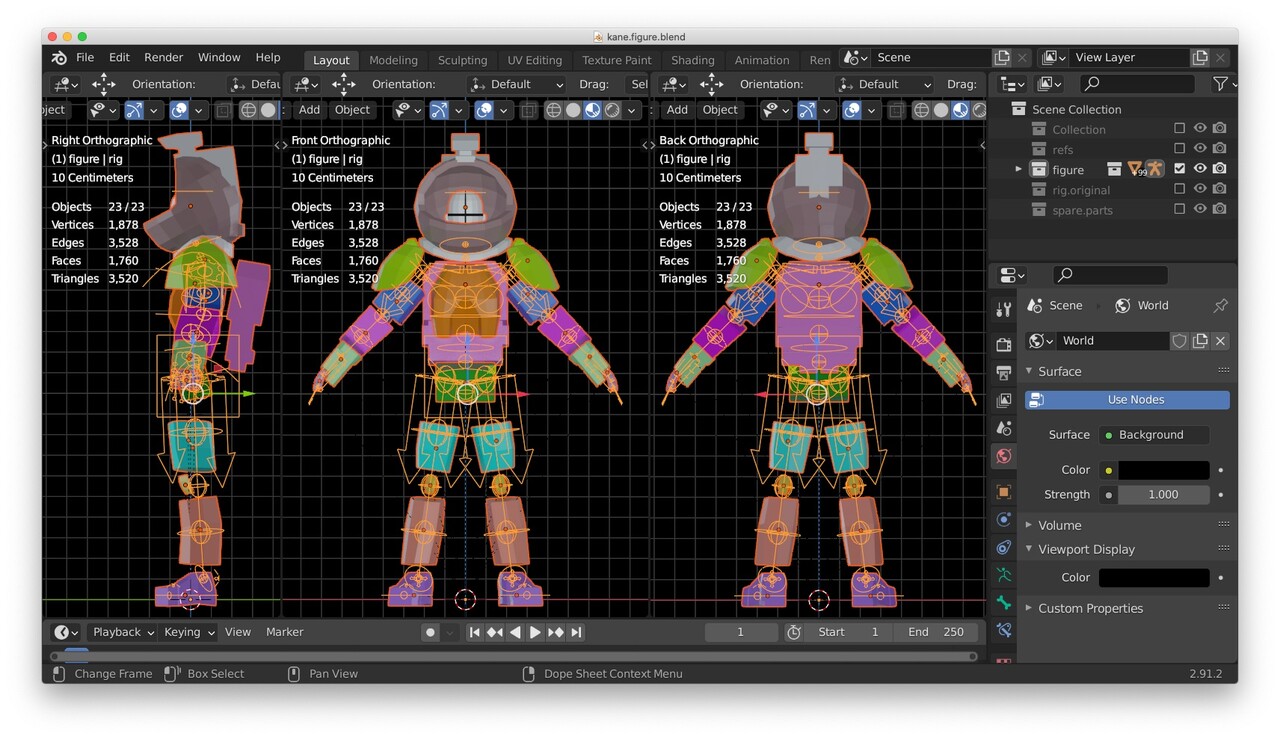

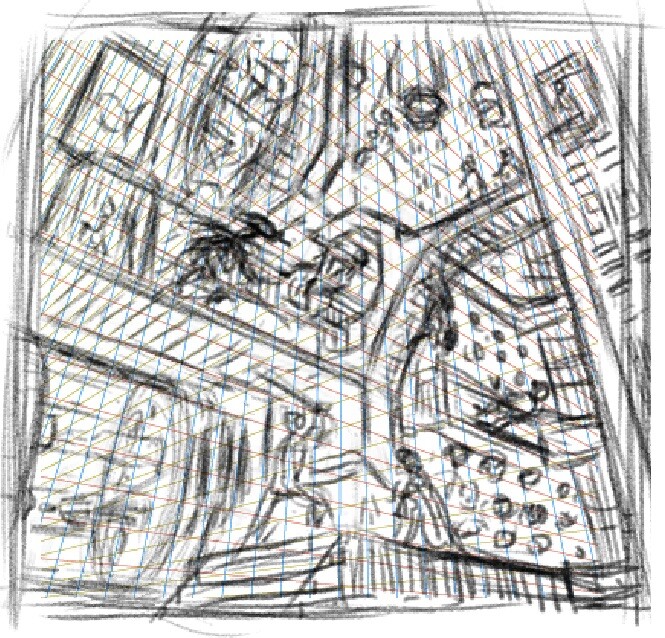

I began by setting up the renders of my reference figures as base layers in Photoshop and got to work drawing more fully-realized character sketches on top of them.

I wasn’t going to bother with color yet; grayscale drawings would be just fine to establish all the costume details. I was also not particularly concerned with lighting—I still wasn’t sure if I wanted the characters to only be lit by the light sources that existed exclusively in their world—so I was only going to use enough modeling in the drawing to give an indication of the structure of the forms, not the way they were lit. Color and light were both feeling like issues I wasn’t close to thinking about yet. I had a lot of drawing to do first.

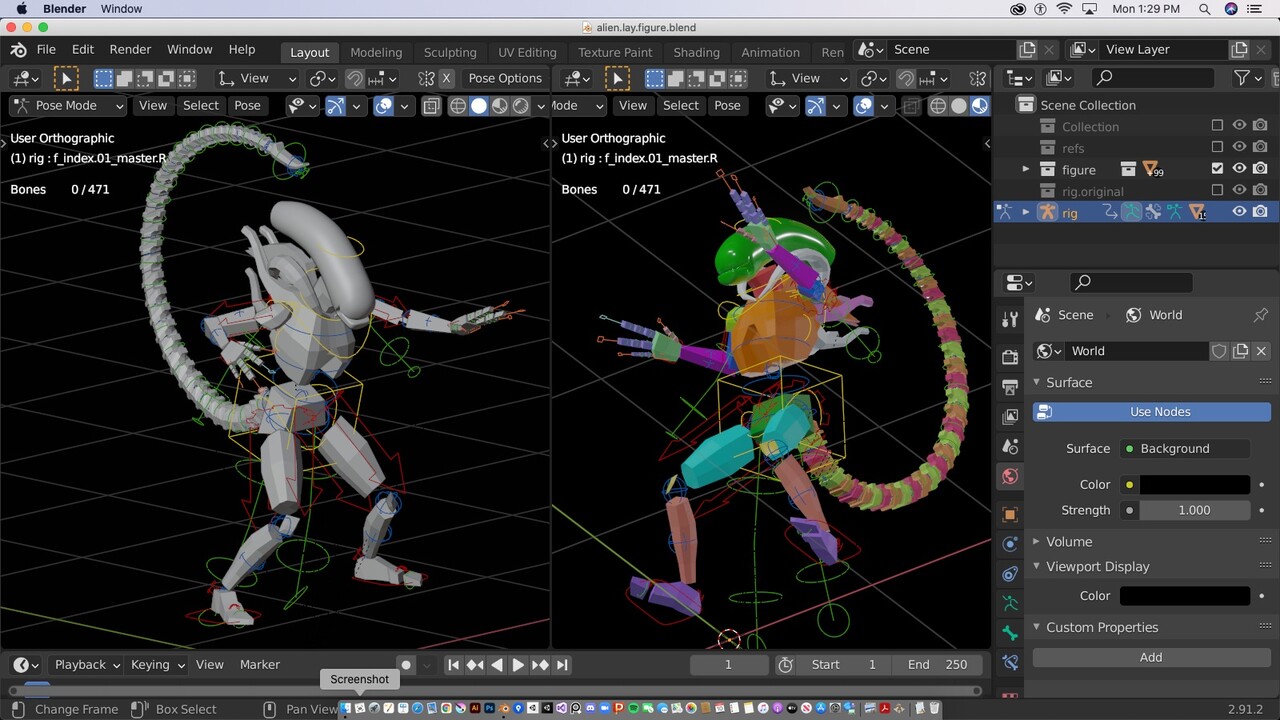

I figured the best character to start with was the xenomorph from Alien—I didn’t want to get too bogged down with trying to create a likeness right off the bat, so the alien seemed like a good way to get into the groove of drawing again after all the modeling and vector work.

All of that preliminary work immediately felt worth it the minute I started drawing. The reference render I’d made of the Alien in the correct perspective and pose made it possible to finish the sketch in a couple of hours. I’d rendered each figure 4 times larger than the size it would be in the final image to give me a comfortable size to draw details, so I knew I had all I needed in the sketch (especially since the alien was going to be primarily a silhouette.)

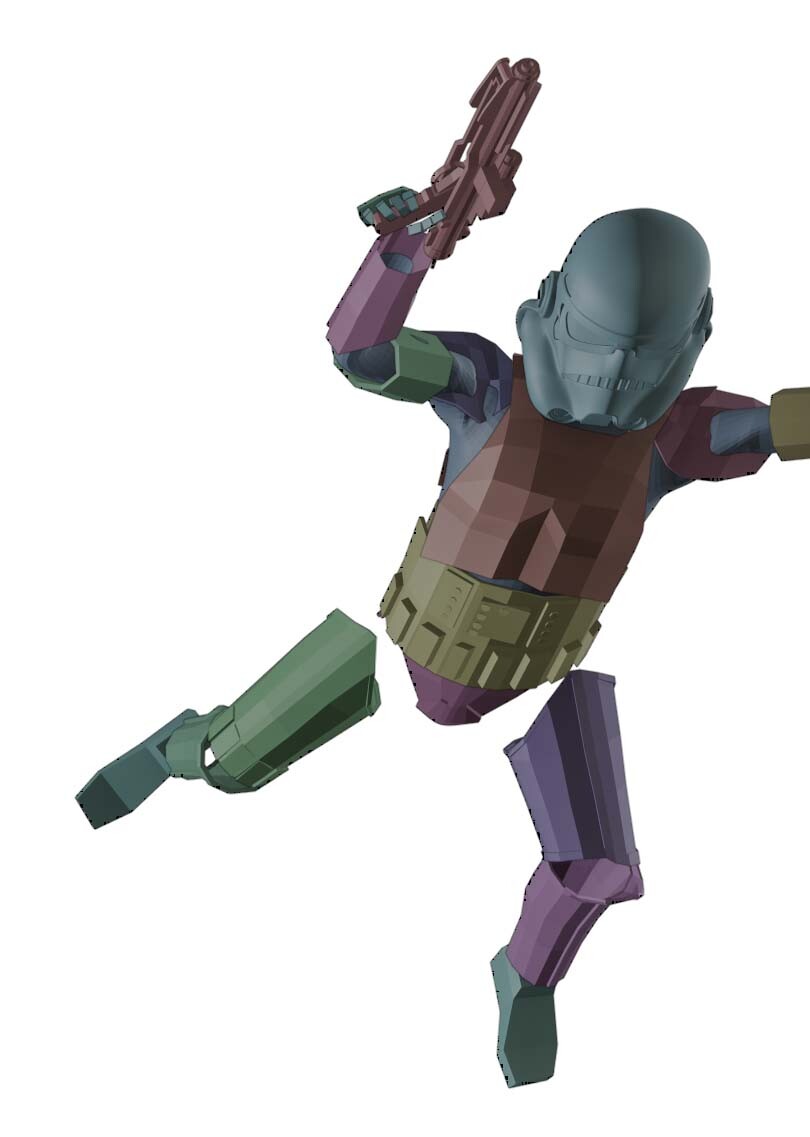

The most logical sequence to drawing the sketches seemed to be to complete all the characters from one world and move on to the next, so the next one up was Kane—I wanted to leave Ripley for last because the challenge with Kane seemed to be similar to drawing the Alien—all the detail in his spacesuit was going to require most of the attention, so capturing a likeness wasn’t going to be as big a priority.

Now that I had a couple of characters in the books, it was time to tackle the first attempt at a recognizable human. I wasn’t going to drive myself too crazy with trying to create portraits of the stars of the respective films/shows—the main point of the image was the space being created rather than the characters in it—but I still wanted to get a close enough likeness to them to make it easy to read who these people were and where they were coming from. I wasn’t completely satisfied with my Ripley sketch, but it was close enough for the stage the image was in for me to move on to other characters. With all my years working in Illustrator, I’ve come to prefer sketches that aren’t completely comprehensive—if a sketch is too complete, creating the final art becomes too much like mindless, tedious tracing over a template. The sketch served its purpose in giving me as much information as I needed to move forward to the next step.

For now, the next step was moving on to sketches of the Star Wars characters.